Friends, if you’re in my unfortunate company these past few hard weeks, I’m sorry. I know how it feels to have the dream ripped away.

I know what it is to lose a job I loved—and to lose more than a job, but a purpose. I know what it is to have no recourse; to find my options suddenly narrowed when I thought they were already as narrow as they could possibly get. I even know what it is to find myself suddenly an enemy of the official narrative of the government, to search in vain for a non-existent safety net, and to have no idea where to turn, or what to do.

For four years, I was a trail worker. I spent most of that time working for the U.S. Forest Service, chasing a career that seemed a perfect match, an answer to my life’s search for meaningful work, and also a hopelessly long shot. From my very first season as an AmeriCorps volunteer, I saw the doors already closing to a long-term, permanent career as a steward of our public lands. By the early ‘20s, funding for the agencies was on a three-decade decline. Forests and districts combined and consolidated, jobs dwindled, and opportunities for the security of non-seasonal employment grew increasingly out of reach. But I was determined. I uprooted my life to take my first seasonal job, then another, and another. I worked long, brutal days and even lived out of my car. In time, against the odds, I saw the dream come closer into view. During my final season, an agency hand extended the permanent job offer I’d always wanted. As I reached out to take it, I watched it melt into air.

Of course, readers of this publication know that, compared to many of you now facing the end of your agency careers, my circumstances were slightly different.

The dream ended for me in late 2023, roughly a year and a half before Donald Trump and his Nazi czar of government collapse unilaterally dismissed thousands of federal employees in the National Park and U.S. Forest Service. For me, it was the historically new, historically disabling, and politically inconvenient illness known as Long COVID; I’ve written about it before. But I am not here to shift the limelight or steal valor from you who’ve lost your jobs in an equally historic low point in the history of our country. The fact is that our stories, our struggles, are not different at all. I am here to speak of solidarity.

To those who have not followed the politics of public lands management for the last few years, news of the mass layoffs of rangers and land stewards might have come as a shock. But I suspect few of you who lost your jobs this month did not see something coming. Even my own illness a year and a half ago, despite being obviously a freak and unpredictable tragedy in my own life, took on the pallor of an omen as the crisis in American land management unfolded in the months that followed. To recap:

Before I was even moved out of my seasonal housing, my last district consolidated with the neighboring one into a “Zone,” with consolidated senior staff to boot.

That fall, the anticipated “permanent seasonal” hiring process nearly fell apart, first in the agency’s timber departments, and then in trails.

Six months after I left, the agency revealed the scope of its budget crisis and instituted the “hiring pause” that it assured my friends was not a freeze.

A year later, the end of all seasonal positions entirely.

And now here we are. For the last two weeks, my personal social media feeds have been a cascade of all of my friends getting fired, my friends’ friends getting fired, new permanent seasonal hires getting fired, longtime permanent employees getting fired. We are all now shipwrecked victims adrift on the wreckage of the rapidly collapsing American environmental management state. I simply happened to fall overboard just before it sank. (To be honest, I’m still trying to figure out if this was good or bad luck.)

I feel a certain responsibility to speak to my new shipwreckmates, having gotten something of a head start in processing and moving on from the grief, the loss, and the disappointment of losing my dream job. Indeed, so many of my laid-off comrades’ posts have used the words “dream job” that I’ve lost count. I don’t believe many people who have not been in our position can quite understand what we mean by this. In our broken world today, a job is rarely more than a necessary evil at best, and one only differs from another in the size and viciousness of that evil. At the agencies—even our modern understaffed, underfunded, mostly captured-by-industry agencies—it was different.

Whether you were a trail worker, a wilderness ranger, a forestry or wildlife technician, or any of the number of honest, important, fulfilling jobs that once made up our public lands agencies, what you have lost is a career that may have seemed to defy the cruel logic of American work. Everywhere you look in America today, everyday people are overworked and underpaid, precarious, underinsured, living paycheck to paycheck. True, all of these were a feature of most of our agency jobs as well. But in the agencies, we had this difference: what we did was undeniably, unimpeachably useful. We were public servants—not a title that most workers can claim. We went to work every day not to turn a profit for ourselves or (more likely) somebody else, but simply to serve the people.

Certainly, the perks of fresh air and access to some of the continent’s most beautiful natural landscapes gives the pain of layoffs an added sting. But despite the spectacular images of wild forests and mountains and rivers in all of my comrades’ recent lost-my-job posts, I don’t think the pain our field is now experiencing has all that much to do with its rugged scenery. We are all too familiar with the flip side of such jobs: the dirt, the injury, the homesickness, the bullshit paperwork, the close calls with sharp blades and power tools. Public lands work is a love/hate affair in the best of times. And we know better than most people how to access ample outdoor adventure and recreation in our free time, without these hardships.

No, what we are mourning—what I’ve been mourning since illness made me unable to walk much more than a mile into a forest—is not the dream of working outside, but the dream of spending your life working for something that is good, something precious and priceless and in desperate need of vigilant protection. That is why we put up with not only the hazards and hardships, but the low pay, the precarity, and the risk that it might not all work out.

It is clear to me that this ethic of stewardship and service, and not simply jobs on an agency budget, is exactly what Musk, Trump and their allies seek to torpedo into oblivion with these layoffs. And it is clear, like I’m sure it is clear to all of you, that this attack on everything that public lands stands for has been going on for a very long time.

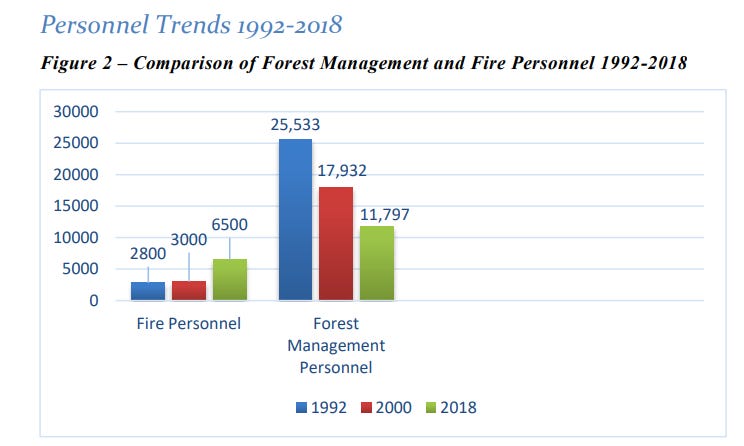

Even before I got sick, I had heard of and met scores of people whose dreams at the agencies had collapsed. As I say all the time, the U.S. Forest Service lost half of its non-fire personnel between 1992 and 2018. Over the same period, forests, districts, and other units have been consolidated “to the point of failure,” often through opaque bureaucratic mechanisms that even researchers cannot track. In the meantime, the agency has stumbled through scandals like the wildland firefighter pay raise and workforce crisis, the failure of old-growth protections, and waves of litigation across the country. More than one former agency employee—usually older, who still remembers the good old days—has joked to me that the agency seems to specialize in producing disillusioned, radicalized former employees to sue them over NEPA violations. (Why all the NEPA violations? Hasty reviews due to not enough staff.)

The point of all this is not that the Forest Service is a bad agency. I could spend an equal amount of time discussing the patient chipping-away of the Park Service, Fish & Wildlife, and the BLM by the same forces. Nor do I want to imply that the people who remain employed in the agencies are doing a poor job. As we know all too well ourselves, people stay in the agency to help right the ship, to hold things together by whatever means necessary until the good times (GAOA, Infrastructure Bills, etc.) come back again.

What all of us—the former employees, the current employees, the lovers of public lands everywhere—need to realize is that we are at a turning point, if we haven’t been there already. Shifting baseline syndrome, commonly cited in discussions of ecological decline, is well at work on all of us federal workers here too. Gradually at first, and now in cataclysmic shocks, the agencies that protect our public lands have been attacked, pillaged, sold to the highest bidder, and abandoned. They may already be as functionally extinct as the North Cascades grizzly, the red wolf, or the American chestnut. We must not allow their extinction to become final.

To those who have only just lost their jobs, perhaps some of this strikes you as too extreme. I recognize that for many of you, the loss is still fresh, and believe me when I say that I understand the immensity and scale of your grief. It took me a long time to see a version of myself and my future that did not feature my USFS uniform. To some extent, I will always be a trail worker. But to use the phrase we hear all the time: Let this radicalize you. All that really means is, let this free you. You no longer have to worry about losing your job for speaking out about this, after all. So why not start now?

When the grief yields to clarity—and it will—I hope you will take a good, honest look at these last few years in the American public lands system and fight back. In fact, many of you already have. Online there are thousands of posts circulating with instructions to contact our representatives in Congress to make your voice heard. In my next post I’ll talk about why I worry that will not be enough—Republicans may have defunded the agencies, but Democrats have repeatedly failed to restore them. Direct action, I think, would be more fruitful. What better way to resist a mass dismissal of public lands workers, for instance—a strange perversion of a worker’s strike—than, say, occupying those lands, staging demonstrations and protests in the name of the people?

But I’ll save that for next time. For now, remember that we are not only fighting for our jobs. We are fighting for a dream. It is not the dream of merely a cool job in a national park, for a wage earned by carrying a crosscut saw or a ranger’s badge, but for a truly public system of public lands, managed by and for the people, both for us and the generations to come. This is what we are losing, right now, if we do not stop it. That is what we must work to restore. That is the dream. And the good news, friends, is that that dream is only just beginning.

This was excellent and deeply sad. I know all of what you write but I hurts to read it all the same. It’s taken me a week to draft my own write up about this and I’m still not done because the words aren’t right.

Federal bureaucrats haven’t been practicing any real land management for nearly fifty years now. It was at about that time that environmental extremists began taking over the forestry schools, most of which are Back East, and most of whose professors have never worked in the woods or even spent so much as a night there.

The Forest Service men who KNEW the woods - many of whom had come in via Roosevelt’s CCC program - were getting old and retiring. They were replaced by fresh young faces who knew nothing, and were unwilling to learn.

Soon, we had Real Forestry being blocked by unending EIS “studies,” ever-increasing Wilderness set-asides, and the foolish goal of forest “preservation.”

You cannot preserve a living thing. Forests are living things.

Now, the hallowed Gifford Pinchot concept of Multiple Use has given way to single-use: recreation, and in many cases, no use at all. And the result is as predictable as rain in Oregon: catastrophic wildfires burning up thousands of acres, instead of Wise Use that removes a few hundred acres of wood here, a few hundred there, and keeping the forests healthy and continually producing valuable fiber and other products for people to actually use.

Don’t cry for the misguided ideologies of the past: they have led only to disaster. A new bunch is in charge of public lands now; people who actually understand land management, and the current purge of Leftist ideologues will be complete soon. Then, and only then can we begin to actually manage our vast public lands in the way that was lost fifty years ago.

Public lands in America have a bright future ahead.